This is the second article in the series “Developing our programming language in Java”, first article can be read here.

At the current stage, we have an interpreter capable of executing the commands of our language. However, this is not enough if we want to check the code for errors and display them in a clear way to the user. In this article we will consider adding error diagnostics to the language. Conducting error analysis in your own programming language is an important step in language development. Using powerful tools, such as ANTLR, allows you to implement rather efficient code analysis tools in a short time that will help you to detect potential problems in a program at early stages of development, which helps to improve software quality and increase developer’s productivity.

Classification of errors

There are different types of errors, but in general they can be divided into three categories: syntax, semantic and runtime errors.

Syntax errors occur due to violation of the syntax rules of a particular programming language. Syntax rules define how statements and expressions in code should be organized.

Example of a syntax error (missing closing quote):

println("Hello, World!)

Semantic errors occur when a program is compiled and even executed, but the result is different from what was expected. This type of error is the most difficult. Semantic errors can be caused by the programmer’s misunderstanding of the language or the task at hand. For example, if a programmer has a poor understanding of operator precedence, then he can write the following code:

var a = 1 + 2 * 3

One could expect the variable a to be equal to 9, but in fact it will be equal to 7. This happens because the multiplication operator has higher precedence than the addition operator. A semantic error can usually be discovered during debugging or extensive testing of the program.

Runtime errors, also known as Exceptions, occur during program execution. Such errors can occur due to incorrect data entry, attempting to access a non-existent file, and in many other scenarios. Some runtime errors can be handled in a program, but if this is not done, the program usually crash.

In addition to errors, it is also important to detect potential problems or non-obvious situations that are not errors in the strict sense, but may lead to undesirable consequences. For example, it could be an unused variable, use of deprecated functions, or a meaningless operation. In all such cases, warnings can be shown to the user.

JimpleBaseVisitor

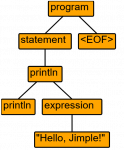

To identify errors and warnings, we need the abstract class JimpleBaseVisitor (generated by ANTLR), familiar to us from the first article, which by default implements the JimleVisitor interface. It allows you to traverse the AST tree (Abstract Syntax Tree), and based on the analysis of its nodes we will decide upon the error, warning or normal part of the code. In essence, diagnosing errors is almost no different from interpreting code, except when we need to perform I/O or access external resources. For example, if a console output command is executed, then our task is to check whether the data type is passed as an argument is valid, without directly outputting to the console.

Let’s create the JimpleDiagnosticTool class, which inherits JimleBaseVisitor and encapsulates all the logic of finding and storing errors:

class JimpleDiagnosticTool extends JimpleBaseVisitor<ValidationInfo> {

private Set<Issue> issues = new LinkedHashSet<>();

}

record Issue(IssueType type, String message, int lineNumber, int lineOffset, String details) {}

This class contains a list of type Issue, which represents information about a specific error.

It is known that each method of a given class must return a value of a certain type. In our case, we will return information about the type of node in the tree — ValidationInfo. This class also contains information about the possible value, this will help us identify some semantic or runtime errors.

record ValidationInfo(ValidationType type, Object value) {}

enum ValidationType {

/**

* Expression returns nothing.

*/

VOID,

/**

* Expression is String

*/

STRING,

/**

* Expression is double

*/

DOUBLE,

/**

* Expression is long

*/

NUMBER,

/**

* Expression is boolean

*/

BOOL,

/**

* Expression contains error and analysing in another context no makes sense.

*/

SKIP,

/**

* When object can be any type. Used only in Check function definition mode.

*/

ANY,

/**

* Tree part is function declaration

*/

FUNCTION_DEFINITION

}

You should pay attention to the value of ValidationType.SKIP. It will be used if an error has been found and already registered in a part of the tree, and further analysis of this tree node does not make sense. For example, if one argument in a sum expression contains an error, then the second argument of the expression will not be analyzed.

ValidationInfo checkBinaryOperatorCommon(ParseTree leftExp, ParseTree rightExp, Token operator) {

ValidationInfo left = visit(leftExp);

if (left.isSkip()) {

return ValidationInfo.SKIP;

}

ValidationInfo right = visit(rightExp);

if (right.isSkip()) {

return ValidationInfo.SKIP;

}

// code omitted

}

Listers vs Visitors

Before moving on, let’s take a look at another ANTLR-generated interface JimpleListener (pattern Observer), which can also be used if we need traverse the AST tree. What is the difference between them? The biggest difference between these mechanisms is that listener methods are always called by ANTLR on a per-node basis, whereas visitor methods must bypass their child elements with explicit calls. And if the programmer does not call visit() on child nodes, then these nodes are not visited, i.e. we have the ability to control tree traversal. For example, in our implementation, the function body is first visited once in its entirety (mode checkFuncDefinition==true) to detect errors in the entire function (all if and else blocks), and several times with specific argument values:

@Override

ValidationInfo visitIfStatement(IfStatementContext ctx) {

// calc expression in "if" condition

ValidationInfo condition = visit(ctx.expression());

if (checkFuncDefinition) {

visit(ctx.statement());

// as it's just function definition check, check else statement as well

JimpleParser.ElseStatementContext elseStatement = ctx.elseStatement();

if (elseStatement != null) {

visit(elseStatement);

}

return ValidationInfo.VOID;

}

// it's not check function definition, it's checking of certain function call

if (condition.isBool() && condition.hasValue()) {

if (condition.asBoolean()) {

visit(ctx.statement());

} else {

JimpleParser.ElseStatementContext elseStatement = ctx.elseStatement();

if (elseStatement != null) {

visit(elseStatement);

}

}

}

return ValidationInfo.VOID;

}

The Visitor pattern works very well if we need to map a specific value for each tree node. This is exactly what we need.

Catching syntactic errors

In order to find some syntax errors in the code, we need to implement the ANTLRErrorListener interface. This interface contains four methods that will be called (by the parser and/or lexer) in case of an error or undefined behavior:

interface ANTLRErrorListener {

void syntaxError(Recognizer<?, ?> recognizer, Object offendingSymbol, int line, int charPositionInLine, String msg, RecognitionException e);

void reportAmbiguity(Parser recognizer, DFA dfa, int startIndex, int stopIndex, boolean exact, BitSet ambigAlts, ATNConfigSet configs);

void reportAttemptingFullContext(Parser recognizer, DFA dfa, int startIndex, int stopIndex, BitSet conflictingAlts, ATNConfigSet configs);

void reportContextSensitivity(Parser recognizer, DFA dfa, int startIndex, int stopIndex, int prediction, ATNConfigSet configs);

}

The name of the first method (syntaxError) speaks for itself; it will be called in case of a syntax error. The implementation is quite simple: we need to convert the error information into an object of type Issue and add it to the list of errors:

@Override

void syntaxError(Recognizer<?, ?> recognizer, Object offendingSymbol, int line, int charPositionInLine, String msg, RecognitionException e) {

int offset = charPositionInLine + 1;

issues.add(new Issue(IssueType.ERROR, msg, line, offset, makeDetails(line, offset)));

}

The remaining three methods can be ignored. ANTLR also implements this interface itself (see class ConsoleErrorListener) and sends errors to the standard error stream (System.err). To disable it and other standard handlers, we need to call the removeErrorListeners method on the parser and lexer:

// remove default error handlers

lexer.removeErrorListeners();

parser.removeErrorListeners();

Another type of syntax error is based on the rules of a particular language. For example, in our language, a function is identified by its name and number of arguments. When the analyzer encounters a function call, it checks whether a function with the same name and number of arguments exists. If not, then it throws an error. To do this, we need to override the visitFunctionCall method:

@Override

ValidationInfo visitFunctionCall(FunctionCallContext ctx) {

String funName = ctx.IDENTIFIER().getText();

int argumentsCount = ctx.expression().size();

var funSignature = new FunctionSignature(funName, argumentsCount, ctx.getParent());

// find a function in the context by signature (name+number of arguments)

var handler = context.getFunction(funSignature);

if (handler == null) {

addIssue(IssueType.ERROR, ctx.start, "Function with such signature not found: " + funName);

return ValidationInfo.SKIP;

}

// code omitted

}

Let’s check the if construct. Jimple requires that the expression in the if condition is of boolean type:

@Override

ValidationInfo visitIfStatement(IfStatementContext ctx) {

// visit expression

ValidationInfo condition = visit(ctx.expression());

// skip if expression contains error

if (condition.isSkip()) {

return ValidationInfo.SKIP;

}

if (!condition.isBool()) {

addIssue(IssueType.WARNING, ctx.expression().start, "The \"if\" condition must be of boolean type only. But found: " + condition.type());

}

// code omitted

}

The attentive reader will notice that in this case we added a warning, not an error. This is done due to the fact that our language is dynamic, and we don’t always know the exact information about the type of the expression.

Identify semantic errors

As mentioned earlier, semantic errors are difficult to find and can often be found only during debugging or testing the program. However, some of them can be identified at the compilation stage. For example, if we know that the function X always returns 0, then we can show a warning if a division expression uses this function as a divisor. Division by zero is usually considered a semantic error, since division by zero makes no sense in mathematics.

An example of error detection “Division by zero”: triggered when an expression is used as a divisor, which always returns the value 0:

ValidationInfo checkBinaryOperatorForNumeric(ValidationInfo left, ValidationInfo right, Token operator) {

if (operator.getType() == JimpleParser.SLASH && right.hasValue() && ((Number) right.value()).longValue() == 0) {

// if we have value of right's part of division expression and it's zero

addIssue(IssueType.WARNING, operator, "Division by zero");

}

// code omitted

}

Runtime errors

Runtime errors are also difficult or even impossible to detect at the compilation/interpretation stage. However, some such errors can still be identified. For example, if a function calls itself (either directly or through another function), this may result in a stack overflow error (StackOverflow). The first thing we need to do is to declare a list (Set) where we will store the functions that are in the process of being called at the moment. The check itself can (and should) be placed in the handleFuncInternal method of processing the function call. At the beginning of this method, we check whether the current FunctionDefinitionContext (function declaration context) is in the list of already called functions, and if that is the case, we log a Warning and interrupt further processing of the function. If not, then we add the current context to our list, and the rest of the logic follows. When exiting handleFuncInternal, you need to remove the current function context from the list. Here it should be noted that in this case we not only identified a potential StackOverflow, but also got rid of the same error when diagnosing error, namely when looping the handleFuncInternal method.

Set<FunctionDefinitionContext> calledFuncs = new HashSet<>();

ValidationInfo handleFuncInternal(List<String> parameters, List<Object> arguments, FunctionDefinitionContext ctx) {

if (calledFuncs.contains(ctx)) {

addIssue(IssueType.WARNING, ctx.name, String.format("Recursive call of function '%s' can lead to StackOverflow", ctx.name.getText()));

return ValidationInfo.SKIP;

}

calledFuncs.add(ctx);

// other checkings

calledFuncs.remove(ctx);

// return resulting ValidationInfo

}

Control/data-flow analysis

For a deeper study of program code, optimization and identification of complex errors, Control-flow analysis and Data-flow analysis are also used.

Control flow analysis is focused on understanding which parts of a program are executed depending on various conditions and control structures such as conditional (if-else) statements, loops, and branches. It allows you to identify the program execution paths and detect potential errors associated with incorrect flow control logic. For example, unreachable code or potential program hangpoints.

Data flow analysis, on the other hand, focuses on how data is distributed and used within a program. It helps identify potential data problems such as the use of uninitialized variables, data dependencies, and possible memory leaks. Data flow analysis can also detect errors associated with incorrect data operations, such as the use of incorrect types or incorrect (meaningless) calculations.

Summary

In this article, we have examined the process of adding error and warning diagnostics to your programming language. We have learned what does the ANTLR provides out of the box for logging syntax errors. We have alos implemented a handling of some errors and potential problems during program execution.

The entire interpreter source code can be viewed at link.